In Defense of Unorthodox Motivations

on utilising that scarce resource in all it's forms + misanthropic apologeticism

I.

If you think about it, motivation is kinda fake.

It's a bit ridiculous just how flaky an emotion it is. Canonically, it's meant to inspire effort; but in practice it often works the other way around, with action itself begetting further action. Grudging workouts are way easier to grind through once you're halfway through. Writing an introduction is the slowest part of the essay1. Getting out of bed is a particularly annoying example. Actually doing it is way easier than the indolent feeling of under-the-sheets-reluctance would suggest.

Nonetheless, there does seem to be a need for the initial jumpstart, a will to action that precedes the first step. And one could be forgiven for thinking that there currently exists a society-wide desire for foolproof motivation. With exhibit A being the entire genre of self-help. And the front page of z-library being another sign.

Pulling up a thesaurus, the first few results for "motivation" provides the following list: drive, excite, inspire, encouragement, incentivize, move, stimulate. All words with markedly positive connotations. Which is seems in line with the popular line of thinking, i.e. that good motives work best.

This popular advice makes a strong case too. Experience and example both show that intrinsic motivation is a pretty strong driver of action. And it seems to lasts a hell of a lot longer too. The extreme negative cases; broken families, worn-out souls, hollow purpose and investment bankers (oh wait, I'm repeating myself); all provide strong warnings against letting the mimetic forces of envy et al. guide one's actions.

Being inspired by an appropriately inspiring figure, driven by filial piety and blood-ties, being led on by the unnering instinct of your heart's true desire or the urge to be a better you, are the more positive (and dare I say, marketable?) motivations that make for heart-warming stories and eventually, movies. Surely, we would all be better off if we did our best to utilise fuel from just these felicitous sources.

Nah, I don't think so.

II.

I say use whatever it takes.

I don't intend for this to be a debate about means vs. ends. I prefer to leave such theoretical pedantry to the professional philosophers. Nobody is out there building the rails for a real life trolley problem. If they are, the easy answer is just, y'know, stopping them. For anyone in the real world, the means are virtually inseperable from their ends.

All I know is that, in their daily war against inertia, some of the most impressive people I know are motivated far less by their grandiose visions of utopia-building or personal ambition than they are by a dozen other,...less than ideal inspirations. They do hope for good outcomes, but the means that get them there aren't particularly praiseworthy.

Of course, this isn't a new idea. Way back in 1776, Adam Smith pointed out (in An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations2) how human self-interest could, in fact, be a good thing. So it shouldn't be particularly surprising that the more undesirable of incentives are able to produce preffered outcomes. Self-interest is pretty boring too, it’s what everyone does most of the time anyway. But apart from that particular incentive, the sheer variety of alternate motivations never ceases to fascinate me.

Take, for example, my favourite teenage economist. As much as he both loves and enjoys the subject now, the origin story is less than rosy. Not so much an example of a boy-intrigued-by-the-depth-and-history-of-the-field as it was kid-who-failed-an-econ-test-amd-decided-to-git-gud-as-vengeance. And did he ever get good. No seriously, his podcast is the only one I’ve listened to all year.

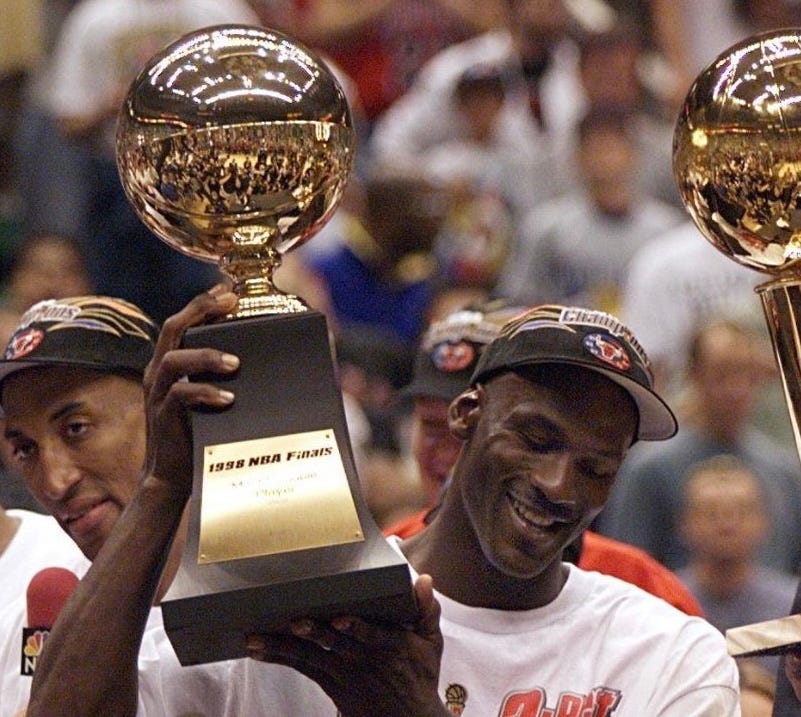

Being fueled by ridicule from leftists? Works for Slava. Going into grad school hell3 and emerging with a PhD just for internet clout? That's how we get a Noah Smith. Needing to be slighted in order to perform historic feats of sporting dominance? That's Michael Jordan for you.

The scholars aren’t extempt from petty glory-chasing either. Even a mathematician as distinguished as Hardy admits that's his earliest efforts at excellence were motivated by the relatively narcissistic desire for victory:

“I do not remember having felt, as a boy, any passion for mathematics, and such notions as I may have had of the career of a mathematician were far from noble. I thought of mathematics in terms of examinations and scholarships: I wanted to beat other boys, and this seemed to be the way in which I could do so most decisively.” - G.H. Hardy

Being afraid works pretty well too, as long as you do an FDR (“The only thing we have to fear itself”) and end up digging yourself out of the initial paralysis. As long as you hate being afraid more than you do the thing you're afraid of, you’ll be okay.

The reason self-coercion rarely works is not because threats are ineffective motivations, but because they're not scary enough. As inconvenient as it is in this case, you just can’t scare yourself. There's nothing you can do to change that, and so it devolves into a hopeless shouting match between the parts of you that are opposed to the thing and the bully trying to get stuff done.

Contrary to popular belief, the main value-add from teachers is not pedagogical expertise, but as a spur to action. It’s easier to get moving when there’s even that tiny minimum of external expectation. So it is with schools too. There’s a bunch of grunt work that school enables that is near impossible to find a good-enough justification for otherwise.

We need external drivers to step in whenever personal desire stops short. It's why being in the military will fix your sleep schedule faster than warm milk and reading mode can.

On first glance, the feeling of falling behind seems like a net negative, one that's responsible for uncountable abandoned starts and discouragements. But if you can be more intentional about it, it’s also fuel to make sure you keep up. Scenius is more rivalry than anything else. Being surrounded by unreasonably high-achievers is good because then at least you know you’re trying. Provided, of course, that you really want to keep up, and aren’t falling into another one of those Girardian hellscapes.

A helpful way of looking at these less-than-pure motivations it is that if you're not using them, they're using you. And you hate being used, right? Right?

If motivation is a scarce resource, we might as well make the most of what we’ve got. Choose worthy ends, and use whatever you must.

A more extreme example is that of the link between traumatic childhoods and genius. Or even the more general cliche of the tortured genius, of coked up songwriters and bipolar philosophers. The romantic idea of suffering for your art is a popular one. While I don't have much personal conviction that such a causal link exists, it's possibility alone makes it a factor worth considering.

III.

Is it sustainable? Perhaps not.

But it doesn't have to be. All it needs to be is good enough. Good enough to get me moving when I'd rather not. Good enough to fill in when the other frameworks fail. Good enough to make a difference on the margin. And a bunch of stuff that gets frowned upon, reproached, or otherwise discouraged is nonetheless extremely effective.

The chip on your shoulder will take you further than most people born into complacency. But isn’t embarrassing to always have something to prove? Only if you let it rule your entire life. Otherwise it’s just a stronger-than-average reminder of what you want.

Being motivated by other people? Lindy. And just plain...nice. One of my favourite example of this is Andre Agassi’s need to play for other people instead of himself. Not so much because being motivated by other people is a particularly unique thing, most people work like that. But because playing for himself just didn't work.

“Agassi isn’t self-motivated. In fact, when he’s only playing for himself, he plays terribly; he only plays well when he is playing for something he cares about: either he’s playing for his staff, who double as his posse of best friends; or he’s playing with the goal of raising his status and wealth so that he has more capital to put towards the school he started for under-privileged children.” - Priya Ghose

Do Things For Yourself gave us the millenials and cat-mom culture. Probably falling fertility rates too, if you care about that kind of stuff. But imagine it as a selfless duty, and you can keep your personal benefits while being motivated by the greater good. Even body-sculpting, that famously narcissistic pursuit, is granted a more charitable interpretation under the frame of uselfish duty.

Doing things you hate just to get them over with works so well it's ironic. Sure, there's the argument that we should be lighting fires instead of filling buckets. But I work pretty fast when I want to never see the bucket again. And a cool thing about buckets is that you can see them filling up as you work.

Jeremy Nixon has a cool list of ways to get yourself immersed into something. The upshot of which is that you need almost irrational levels of motivations to do so, not all of them virtuous. Point #7 (Have an enemy who’s growing faster than you are) is a personal favourite and reminds me of this post by Sasha. If you can’t find/imagine a good enemy to do battle with, Moloch is always a worthy adversary.

I'm also all for harnessing anger, and sheer hatred for the status quo. Harnessing, that is, not giving in to. Do entrepreneurs pick their careers because they love business, or because they really, really hate writing resumes? Few things are more cringe than angry yelling as a reaction, and few forces are as effective as a cold, focused rage. Rage, rage against the rise of Moloch.

IV.

This isn't really meant to be prescriptive.

The only reason I chose to defend this stuff at all is because it hurts no one else. Heck, it doesn't even hurt you unless it’s turning you into what you definitely do not want to be. Notably absent from the previous examples were any mention of the Girardian twins: jealousy and envy, because that’s where I personally draw the line. Not that they aren’t effective motivators in themselves, I just don’t think the trade-offs are worth it in that particular case. Humans are only too suscpetible to be drawn into zero-sum status conpetitions, and I am but human.

Not that mimesis is all bad. Getting good at working with it wisely is extremely useful skill to have.

“I submit that the key to success is to be aware of one’s tendencies, either to be very mimetic or not at all. Then one can harness these tendencies to maximize learning, and not spend all one’s time indulging solitary whims or be governed by mimetic contagion. It’s possible that the greatest amount of learning comes as a result of fluctuating between these extremes.” - Dan Wang

What I do hope to do however, is shift the Overton window of effective motivations. It currently seems to lie somewhere between self-driven and passion, ignoring their less-pleasant counterparts. And hearing that those other motivations aren't worth entertaining is untrue enough that it made me to write a whole essay celebrating the other options. Now there’s motivation for ya.

Raging against false dichotomies is passè now, but it’s still true that most things are never either/or. The choice isn’t passion or apathy, it’s everything in between as well. Doing what you don’t really care about is good, if it gets you the outcomes you want. And adding literally anything else in place of that lack of caring is helpful when you’re grinding through it.

To prove I’m not a complete misanthrope4, I will point out that arguments that blame happiness for complancency are pretty terrible too. Yeah, perfect happiness would be paralysing. Maybe. But we don't have that yet. And we won't ever, unless we build the experience machine or something. Until then, there’s no reason to confuse happiness with catatonia, the most complacent people I know are pretty f-ing sad.

Even with these additional drives, motivation will remain as flaky as ever. Moods are weird things. Attempting to game them for the purposes of productivity or otherwise almost never works. Most people have accepted this. But it can’t hurt to have more tools in the toolbox, as long as you know how to use them.

That’s why I now write the introduction last.

If you think that title’s a bit verbose, you should see the prose.

For what it’s worth, he says it isn’t that bad.

I totally am though.